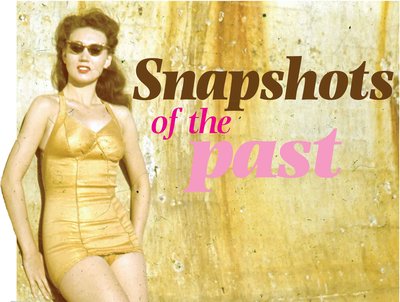

As historian Carol Olten points out in her new book “La Jolla Then and Now,” to be featured at a 7 p.m. signing event on May 7 at D.G. Wills Books, day-to-day changes in urban landscape can easily go unnoticed, while transformations that have taken place in La Jolla since its beginnings in the late 1800s seem monumental when observed over a long time. The book, photographed and co-authored by Rudy Vaca, uses photos to capture the past and present of La Jolla, while explaining and comparing the two. It illustrates how iconic rock formations have weathered or fallen, architectural structures have been replaced or altered and commercialization has proliferated. Standing out among the intriguing changes over the last decade are those involving the people who we cannot talk to, but only observe in the black and white photos that have been left behind. A day at the beach of La Jolla Cove was a much different scene years ago than it is now, and most notably, beach-goers’ attire makes that difference unmistakable. Swimwear evolution A 1910 photo of the La Jolla Cove shows a large group of people sitting on the sand and enjoying a picnic in “Sunday best” clothing — girls in hats and dresses and boys in suits and berets. They don’t drink out of plastic or paper cups, but rather raise china cups to their mouths. No bikinis, no swim trunks, no flip-flops. Swimwear stands out as an ever-evolving custom, and when early attire began to meet changes in modesty, those who chose to wear less met some opposition. While most of those those who experienced it are no longer alive to tell about it, documents reveal there was a 1917 ordinance in La Jolla that banned people from wearing swimsuits in public. Specifically, Common Council Ordinance No. 7056 stated anyone over the age of 10 could not wear a swimsuit “unless there is worn over such bathing suit or swimming suit a coat, cloak or other garment covering the entire person except the head, hands and feet.” The ordinance further stated it was “unlawful for any person having on a bathing suit to sit or lie on that portion of the beach or parcel of land known as ‘The Cove’ in La Jolla, and extending from the Park northwardly for two blocks.” The law carried a fine of “not more than $25” or imprisonment for up to 25 days. Historical reports reveal the ordinance caused much discussion, and was the object of opposition in a San Diego Tribune editorial. In protest, a woman named Frazier Curtis wore overalls over her bathing suit in public, thus staying within the law but “scandalizing the community,” wrote Howard S. F. Randolph in “La Jolla Year by Year,” the first history book on La Jolla. The ordinance ceased to exist by the 1930s. Some photos of beachgoers in the 1920s show women swimming in dress-like outfits with long, loose sleeves. Others show women wearing identical, dark wool dresses that extend to the knee. They walked to the beach in overcoats. In her research, Olten wondered like anyone else how anyone could swim in those fabrics that were worn before stretchy textiles like nylon and Spandex came about. “You kind of wonder how it was to swim,” said the La Jolla Historical Society historian. “The fabric would have just carried you down.” A growing archive The historical society is home to more than 10,000 vintage photos, a collection that began with donations in the 1940s with Randolph’s writing of “La Jolla Year by Year.” Since then, the society has acquired donated photos that range from casual snapshots to professional photographs. The prints have been used in books like “Then and Now,” which went on sale April 11, and they are also used in exhibits at the society’s Wisteria Cottage, located at 780 Prospect St. To show modern-day La Jollans what beach life and attire was like in decades past, for example, the society was lucky to acquire a series of photos taken in the early 1920s of a lady named Daisy Sheppard and her friends posing and enjoying themselves at the Cove. With cameras being a rare commodity in those times, the photos are a rare glimpse into life during the 1920s, a time of great “freedom” and progress in La Jolla, Olten said. “When they were given to us, the owner thought we wouldn’t have any use for these old photos, but we were so happy to get them,” said Olten, stressing that other La Jollans with vintage photographs in their possession should consider donating them to be preserved for posterity in the society’s archives. To donate old photographs, stop by Wisteria Cottage between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Mondays through Fridays or call the society at (858) 459-5335.