B.B. King believed anyone could play the blues and that “as long as people have problems, the blues can never die.”

But no one could play the blues like King, who died May 14 at age 89 in Las Vegas, where he had been in home hospice care.

Although he kept performing well into his 80s and had released more than 50 albums since the 1940s, the 15-time Grammy winner suffered from diabetes and other problems. He collapsed during a concert in Chicago last October, later siting dehydration and exhaustion.

For generations of blues musicians and rock `n’ rollers, King’s plaintive vocals and soaring guitar playing style set the standard for an art form born in the American South and honored and performed worldwide. After the deaths of Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters decades ago, King was the greatest upholder of a tradition that inspired everyone from Jimi Hendrix and Robert Cray to the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton.

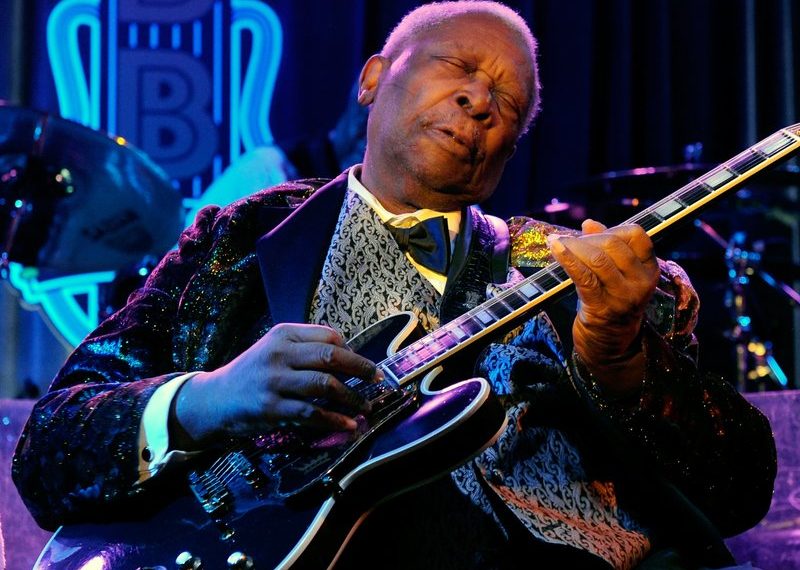

King played a Gibson guitar he affectionately called Lucille, with a style that included beautifully crafted single-string runs punctuated by loud chords, subtle vibratos and bent notes, building on the standard 12-bar blues and improvising like a jazz master.

The result could hypnotize an audience, no more so than when King used it to full effect on his signature song, “The Thrill is Gone.” After seemingly make his guitar shout and cry in anguish as he told the tale of forsaken love, he ended the lyrics with a guttural shouting of the song’s final two lines: “Now that it’s all over, all I can do is wish you well.”

Riley Ben King, whose handle B.B. stood for Blues Boy, was born Sept. 16, 1925, on a tenant farm near Itta Bena in the Mississippi Delta. His parents separated when he was 4, and his mother took him to the even smaller town of Kilmichael. She died when he was 9, and when his grandmother died as well, he lived alone in her primitive cabin, raising cotton to work off debts.

“I was a regular hand when I was 7. I picked cotton. I drove tractors. Children grew up not thinking that this is what they must do. We thought this was the thing to do to help your family,” King said.

His father eventually found him and took him back to Indianola. When the weather was bad and King couldn’t work the fields, he walked 10 miles to a one-room school. He quit in the 10th grade.

A preacher uncle taught him the guitar, and King didn’t play and sing blues in earnest until he was away from his religious household, in basic training with the Army during World War II. He listened to and was influenced by both blues and jazz players: T. Bone Walker, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian.

In the early 1980s, King donated about 8,000 recordings – mostly 33, 45 and 78 rpm records, but also some Edison wax cylinders – to the University of Mississippi, launching a blues archive that researchers still use today. He also supported the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center in Indianola, a $10 million, 18,000-square-foot structure, built around the cotton gin where King once worked.

“I want to be able to share with the world the blues as I know it – that kind of music – and talk about the Delta and Mississippi as a whole,” he said at the center’s groundbreaking in 2005.

The museum not only holds his personal papers, but hosts music camps and community events focused on health challenges including diabetes, which King suffered from for years. At his urging, Mississippi teenagers work as docents, not only at the center but also at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.

“He’s the only man I know, of his talent level, whose talent is exceeded by his humility,” said Allen Hammons, a museum board member.

In a June 2006 interview, King said there are plenty of great musicians now performing who will keep the blues alive.

“I could name so many that I think that you won’t miss me at all when I’m not around. You’ll maybe miss seeing my face, but the music will go on,” he said.

King was married twice and divorced twice. He is survived by 11 children. Four children preceded him in death.

— Associated Press