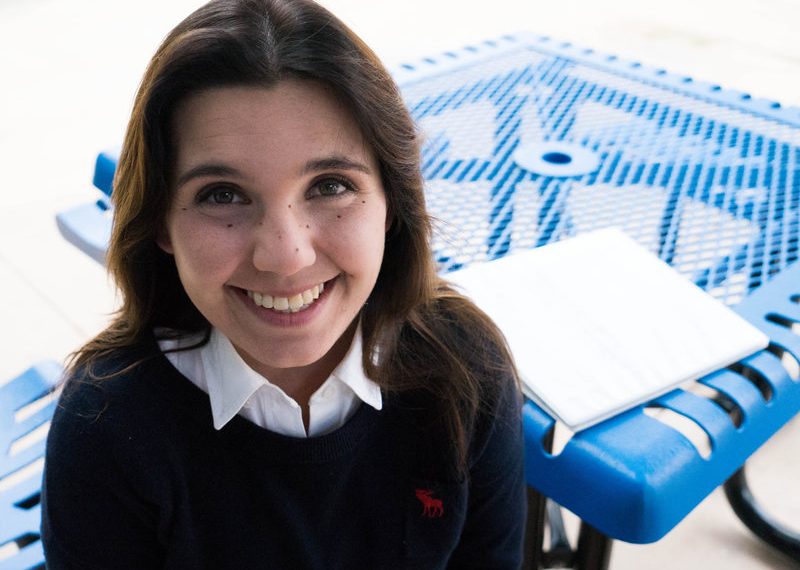

Danielle Franger is a throwback. She reads the Wall Street Journal print edition. She listens to Italian opera. Mind you, she’s 17 years old. “Listening to opera stimulates me,” says the intense, outgoing cheerleader with green eyes. “It helps me focus. When I’m doing homework and I don’t want to spend hours on it, Italian opera helps me. “Some people say I’m an old soul,” the sophomore cheerleader at La Country Day School shares. Those aren’t the only ways she has the depth normally found in an older person. Her Type I diabetes led her to deal with a serious medical condition. Her faith grounds her, with the close-knit support of her mother Rhonda and grandmother Monica. It was the model Danielle’s grandmother set for her own daughter, Rhonda – like the biblical Lois to her daughter Eunice – that enabled the then-eighth grader from Temecula to apply to attend Country Day three years ago. “My mom told me, ‘My mom didn’t shoot down my dreams, so I’m not going to shoot down yours,’” explains Franger. Danielle’s grandfather Thomas died when Rhonda was 14, and Monica raised her three children as a single parent and put all three through college. Rhonda makes the round-trip drive from their home in Temecula to La Jolla every day so Danielle can attend LJCDS. She works in the fashion industry, and she has flexibility that enables her to work around the commutes for Danielle. Franger takes a good-natured ribbing about what a hard date she is due to her medical history, seeing the humor in a pretty grave situation. Last year, Ryan Tobin, who was going to accompany her to the Homecoming dance, got a call from her mother at 5 p.m., a short time before the dance was set to begin. The couple was going to meet at the Hyatt in La Jolla, the site of the dance, since Rhonda had to drive Danielle to La Jolla. Her mother told Ryan that Danielle was very sick and wouldn’t be able to go. What had happened the day before was that Franger told her mother, “I don’t feel well. My heart hurts. My chest hurts.” Her mother told her she didn’t think she should do cheerleading at the Torreys’ Homecoming football game that night. So she went home after school. The next morning, “It’s my Homecoming dance day. I’m a girl,” the sophomore recounts in spellbinding detail. “I needed to get my hair done, my nails done.” Her mother noticed she was slurring her words. Danielle wasn’t aware. In the afternoon, she took a nap to try to rest up for the dance. “I didn’t wake up,” Franger says. “I had a seizure. My mom picked me up and took me to Temecula Hospital.” She now can tell you the exact date all of this was happening: Oct. 26, 2014. She had just turned sweet 16 12 days before. The ER doctor said Danielle had to be airlifted to Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. Michael Gottschalk, an endocrinologist who now knows Franger’s case well, told her mother she was an hour away from going into a coma and that there was a “50-50″chance of her surviving, according to Danielle. “We’re going to save your daughter,” he told Rhonda. They did. She was diagnosed with Type I diabetes. She recovered enough to leave Rady four days later. She learned to give herself insulin shots three times a day and to test her blood insulin level with a pinprick in her finger. A funny thing happened when she first arrived at Rady after being Life-Lined by helicopter to ICU. “I was really out of it,” she says. “My mom says I was still talking. The first doctor at Rady said, ‘Call me Dr. Joe.’ I looked at him. I couldn’t really see him. I said, ‘Dr. Joe, like cup of joe?’” She went to cheer practice Thursday and cheered at the Torreys’ football game that Friday night – this is a highly motivated girl. Two days later, on Sunday, her chest felt tight. She went to her family’s church, Reliance, in Temecula, was anointed by those praying for her and received prayer. She returned to Rady that day, and she was diagnosed with an insulin edema, which she was told is a rare condition that affects one in 3 million people. But for the next six months, she experienced symptoms while controlling her newly diagnosed diabetes. It culminated in April of this year at school, when in French I class at 10:15 a.m. a school administrator had to call 911. Franger, who says she wants to relate the details of her story “because it’s a part of me,” had a ghostly look. So “girl interrupted” was playing out her medical struggle in front of her fellow students. No wonder she says, “Oh, yes, my classmates know my story.” Ryan, her to-be date at Homecoming, sent her flowers at the hospital. Puffed up with fluids her body wasn’t getting rid of, she was found to be allergic to insulin, another rare situation. So that was resolved, and Danielle takes diuretics “to fool my body into getting rid of fluids that it doesn’t want to get rid of.” This past Oct. 26, at 10:48 p.m., marked her one-year “diversary” (diabetes anniversary). That day, she celebrated with Gottschalk. She has a photo of the two celebrating together in her phone. As a result of her Rady doctor’s care, she switched her career goal from journalism – she loves reading – to medicine. She was able to attend this fall’s Homecoming dance with another student, Lexi Watkins. “She is my best friend and helped me a lot through being diagnosed with Type I,” Franger says. Her cheer coach, Kathy Davis, says Franger exhibits a “great attitude” through her recent medical struggles. Cheer, which at Country Day takes place during the fall, has its challenges. “Cheer and exercise in general is very hard to manage with Type I diabetes,” Franger says. “There are many lows and times where I can’t cheer because of my health, but being a part of the team and being able to cheer when I can has been really rewarding after being diagnosed.” Cheer takes place only during the fall because several squad members go on to play sports and participate in other extracurricular activities during basketball season, not leaving enough cheerleaders for a full team. Her being highly organized helps her in taking her shots and doing all the other things she has to do. She already is “taking five years to do four years of high school” because of her medical crisis last year. She should be a junior, but she is repeating her sophomore year. Even now, there are times she has to leave school during the day if she doesn’t feel well. “It’s hard,” she admits, “and it takes a lot of effort to connect with my teachers on making up the work. But I’m passionate about school, and it’s important to me to get everything done. I’m very organized, which helps as well. The teachers at Country Day are very understanding and work with me as well.” Getting through the mental part of the illness is often the hardest part. One of her teachers, Daniel Norland, gave her a real shot in the arm with moral support. “I’ve had Mr. Norland for history for three years,” Franger says. “He gave me an article on resilience. Soldiers coming back from war go through counseling. They are identified as having either learned helplessness or learned resilience. Mr. Norland told me he saw me as someone who is resilient. That really makes me feel good to know how people see me.” Family is a powerful bond. Danielle has enjoyed traveling to Europe with her mother, whose work in the fashion industry takes her abroad. Another avenue for time together is playing cards with her grandmother. “We love playing cards together,” she says. “She also taught me how to cook. I always cook holiday meals with her.” Having faced her mortality and come through it, and now being an overcomer in moving ahead in her studies toward her goal of medical school, Franger’s dream schools are Brown or Georgetown. “I like the East Coast,” she says. Brown, she adds, has a pre-med program whose entrance pretty much guarantees getting in its medical school also. Though Franger wouldn’t have chosen to get sick, she realizes that this challenge at an early age has forced her to dig deeper and find ways to deal with it – in her resilience that others recognize. She is highly verbal and is still processing her medical reality as she continues to live it. Franger’s life experience gives her the opportunity for insight into others’ struggles and compassion for their difficulties. Henri Nouwen, a Dutch cleric, would call her a wounded healer.