Sometimes the answers to all your questions about your house show up in your mailbox

Miguel Bueno | Visitas a domicilio

Every house tells a story. Some speak louder than others. Some have more interesting stories to tell. And some, however slight their appearance and quiet their demeanor, have something bigger to say: a story about the life and times of the people who lived there or, even, a story about you and me and the world we live in today.

Such was the case with Tom Prokop and Barbara Aste’s modest bungalow of indeterminate style on a canyon overlooking North Park’s swooping Juniper Dip. Tom already knew the house held some secrets. He’d peered inside the walls some 28 years ago when trying to wrestle the place back into shape after it had sat empty for more than a year because the previous owner had died. The framing wasn’t exactly by the book, and there were other oddities: Every window, all 23 of them, was exactly the same size (and chewed up in exactly the same way by termites). The roof was of an unusual design — with ten-foot-tall ceilings cantilevered along the two long outside walls. The ceiling texture was strange, with little concentric swirls in it — a little bit like the swirling brush strokes in Van Gogh’s Starry Night. The interior walls were built directly on top of the plank fir flooring. The roofline was simple, with a single front- and back-facing gable. And the studs inside the walls had writing on them. “The marks were different from what usually comes on lumber,” Tommy, now a retired contractor, says. If anything, the writing had a vaguely military appearance.

Which made sense. Since the neighborhood historian — or, as Tom calls him, “The old guy across the street,” — claimed that the house had been built of surplus lumber from a decommissioned military base. But despite its quirks (or maybe because of them) the house met Tom and Barbara’s needs. It was simple, unpretentious, with a big garage for Tom’s tools and a big canyon for their dog. In short order, they bumped out the kitchen, adding a breakfast nook seating area with a canyon view that became a popular place for friends to gather when Tom, an avid fisherman and expert (if unconventional) cook threw together the occasional weekend feast — which seemed to happen every weekend. The house was always full of life, friends, food, drinks and dogs — and that westerly sunshine that is essential to the good life in Southern California. The years went by and the house remained a bit of a quiet mystery. Then shortly after the first of this year, a fat brown envelope showed up in their mailbox. It was postmarked December 31, 2013 — a date that said something about unfinished business and a self-imposed deadline.

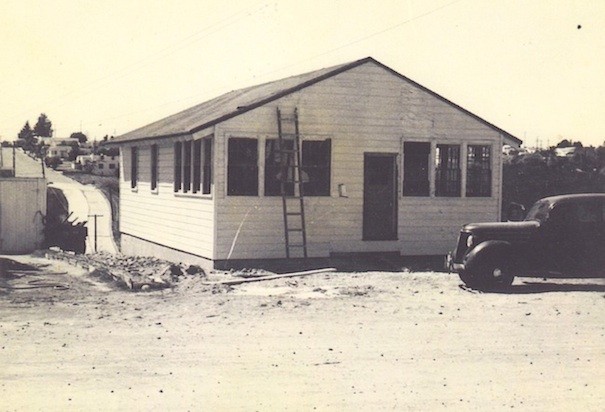

The son of the original owner wrote the letter and, as he explained, the house did, indeed, have a military provenance. In fact, it wasn’t just built of surplus parts from a military building, it was a military building. Inside the envelope was a copy of an application for the building permit, which identified the building as number 43 (Mess Hall), from Camp Callan, a World War II-era military training facility. Camp Callan was built on 1,282 acres of leased land near the present-day site of the Torrey Pines Inn. Construction on 297 buildings covering 23 blocks began in November of 1940. By January 15, 1941 troops were already moving in. During the camp’s busiest period, between March of ’42 and June of ’44, 15,000 men cycled through the facility every 13 weeks. To put things in perspective, the population of San Diego in 1940 was only 203,000. So in two short years, more than half the population of San Diego trooped (literally) through Camp Callan.

The camp was decommissioned on November 1, 1945, and the facilities were declared surplus. There were firing ranges, swimming pools, barracks and cantonments, a 910-bed hospital, offices, five-base exchanges, three theaters, five chapels, support buildings, storage buildings, a landfill and, with thousands of mouths to feed, probably a mess of mess halls. The City Council negotiated with the war department to acquire most of the Camp Callan buildings, which numbered about 500 at the time. The price was $200,000. The City then sold the buildings, pocketing about $250,000, using some of that surplus to finance the War Memorial Building in Balboa Park. Pieces of Camp Callan ended up all over San Diego — the buildings were recycled as churches, commercial buildings and, according to Wikipedia, thousands of homes, including Tommy and Barbara’s house on Westland Drive. The methods and materials developed on bases around the world were used to build housing tracts around the country, under the direction of the Federal Housing Administration, financed by the G.I. Bill, purchased by millions of veterans to make a home for a generation of Baby Boomers like Tom and Barbara — and me and perhaps you, too.

The contents of the envelope that showed up in January of this year solved a number of history mysteries. There was a receipt from R.E. Hazard for $350 (the cost of moving the building). There were photographs of the street being paved (in 1951), photographs of the garage being built (from a kit, in 1953), and an account of how the building was transformed from hall to home over the course of 18 months by the homeowner, a Navy veteran who, like other decommissioned sailors was given first dibs on the decommissioned buildings. Materials were so scarce in 1946, that everything — plumbing, electrical, doors, sinks and cupboards (even the nails) — was salvaged from the remains of Camp Callan. Mom straightened the bent nails. Dad hammered them in. Son looked on in awe (he eventually became a real estate broker, as his letter explained). It took 18 months to outfit their part of the former mess hall with walls, closets, doors, a bathroom and kitchen. Those mysterious swirls in the ceiling? Those were done by the homeowner/builder/artist, with his fingers — apparently even trowels were hard to come by in post-war America.

The house has continued to evolve since then. Tom replaced the rotted windows, shingled the outside, put down an oak floor on top of the old fir planks and expanded the kitchen as soon as he closed escrow back in 1986. He expanded the master bedroom, adding the much-desired walk-in closet and his-and-hers bathroom. Since then, he’s enlarged the deck and built more storage below it. When he first saw the house, back in the 1980s (he’d done work for the former owner), it was the contractor-sized garage the attracted him. Now that he’s retired, he’s come to appreciate the high ceilings, the canyon quiet, and all 23 of the identical, restored windows. Seventy years ago those standard military issue windows would have provided ample illumination and ventilation for hoards of hungry young diners getting their first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean. Today they just let in plenty of light on a house that’s finally revealed most, if not all, of its mysteries.