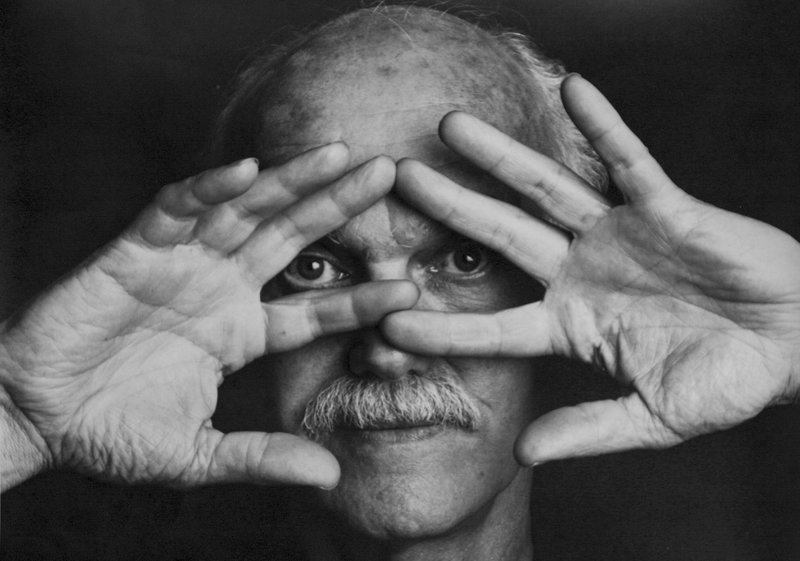

Richard Nixon, such as he was, called psychologist Timothy Leary “the most dangerous man in America.” Other people felt the same – amid his legendary experimentation with psychoactive drugs, Leary would see time in 30 jails during the 1960s and ’70s. Controversy also dealt a blow to his livelihood; he and fellow researcher Richard Alpert left their Harvard University teaching positions in 1963 (Alpert was let go for dispensing a drug; reports conflict as to whether Leary was fired or quit). Fade to 1996, the year Leary died, at age 75. Alpert would eulogize his friend as “my first profound spiritual teacher” – and he knew of what he spoke. Also known as culture figurehead Ram Dass, he got the latter name (Hindi for “servant of God”) during his travels to Nepal and India. He would write “Be Here Now,” the 1971 book on spirituality and meditation; in 2014, he was featured in the film “Dying to Know: Ram Dass and Timothy Leary,” which explores death, faith and the men’s unique spiritual bond. You can see the movie, part of the 26th annual San Diego Jewish Film Festival, on Thursday, Feb. 11, at the David & Dorothea Garfield Theatre in La Jolla’s Jewish Community Center; it will show again on the 14th at the Clairemont Reading 14. The Gay Dillingham-directed entry is particular to this event because Alpert, now 84, is Jewish – and it’s only one of some 40 films that explore the concept of Judaism in popular thought. Other entries will be shown between Feb. 4 and 14 at La Jolla’s ArcLight Cinemas and at venues in Carlsbad and San Marcos. The festival’s PR material touts the event’s “Jewish-themed” aspects, those that reflect Judaism as both a religious and cultural marker. Craig Prater, film festival director, called “Dying to Know” an ideal expression of each facet. Alpert’s religion, for example, fueled his eventual embrace of Leary’s tenets – on top of that, everybody in our culture knows those guys’ names. “We have so many international film groups that may or may not be Jewish,” Prater said, “but they’re interested in learning different cultures that make their film viewing experience broader. I believe that is what makes a Jewish film festival unique to other festivals. So many of our films refer to specific history down through the years, cultural things that may influence storylines. Same with Italian film. Some of them might emphasize food or something, but like Jewish film, the history is so much greater.” Indeed. The first mention of Judaism dates to two centuries before Jesus Christ, and history takes it from there. The faith and its cultural components have outlived some languages and countries amid dizzying evolutions in music, art, politics, war and religion. In “Dying to Know,” for example, Alpert explains that his strict Jewish upbringing led to his friendship with Leary and a larger view of the religious experience. “I came out of the Jewish faith,” he had said at Leary’s eulogy, “and when I met Krishna, I was just flabbergasted that God would be singing and dancing and playing tricks on [Krishna’s homies]. It just didn’t compute.” On the other hand, he said, fate would eventually lead to his embrace of the faith. “My belief,” he told the Religious News Service in 1992, “is that I wasn’t born into Judaism by accident, and so I needed to find ways to honor that. From a Hindu perspective, you are born as what you need to deal with, and if you just try and push it away, whatever it is, it’s got you.” If Alpert’s story isn’t exactly ripped from the headlines, Mideast conflict certainly is. The film “Rock in the Red Zone” is a case in point – it focuses on the Israeli town of Sderot, at once the birthplace of a revolution in Israeli rock music and a constant target of mortar fire from the Gaza Strip. “Younger audiences zero in on this one,” Prater said. “The rock stuff gets their attention, but there are so many scenes involving risk-taking in the areas where anything can happen at any time.” The town’s many pleasant public art pieces, as well as its bus stops, double as bomb shelters – yet its musical spirit survives. So too does Judaism’s place in the human experience. The world’s 14 million Jews make up less than 0.2 percent of the global population, yet their mark on American society is as phenomenal as death, the core topic in “Dying to Know.” “We’ve moved (dying) from ICU wards to hospice and then maybe to something deep and profound,” Alpert says, “but [for Leary] to make it fun? What chutzpah!… [That’s] a major statement for this society.” And amid his trials with society and faith, Alpert has an infallible take on the afterlife, born of a uniquely Jewish perspective. “If I had to choose between suffering and joy,” he asserts, “boy, I know where I’m going. I’m joy, joy all the way.” For a schedule of films and more on the festival, see sdcjc.org/sdjff/.